The "Roles" of Mi'kmaq Women

“There is a fragility in making broad generalizations about Mi’kmaq women's roles in society. Over the generations they have done everything” (Battiste, 1989). Today, it is often accepted that the Mi’kmaq had a matriarchal society. However, it is difficult to find literature supporting this, as Mi’kmaq records are passed down by story telling, rather than written words. The European settlers would not have recognized a matriarch society, because it would have been foreign to them. Therefore, research is mostly based on knowledge passed down from Mi’kmaq Elders and knowledge keepers. Rather than solely define the Mi’kmaq as a matriarchal society or identify the “roles of Mi’kmaq women”, it is more advantageous to examine the equality that existed in Mi’kmaq society, and the lack of importance in defining gender and gender roles in traditional times.

*Art is a depiction of Mi'kmaq Rock Art: Petroglyphs drawn by our ancestors that can be found within the boundries of Kejimkujik National Park & other Mi'kma'ki historic sites.

Concept of Gender

In examining traditional roles of Mi’kmaq women, we must first look at the concept of “gender”, and the Mi’kmaq relationship to it. “The predetermined natural fact of being created by the Holy Spirit as either a woman or man is of minor importance in the Mi’kmaq worldview. In grasping their total experience, both in our language, legends and in small talk, it must be noted that there is no concern with gender. Gender being a foreign concept, brought to our land by the wood walls of Europe, is a strained thought to the Mi’kmaq worldview. Mi’kmaq concepts do not divide man from woman; the concepts only honour their ordinary efforts as mothers, grandmothers, godmothers, teachers, healers and the like”(Battiste, 1989).

The unimportance of gender labels in Mi’kmaq culture underlines the difficulty in breaking down specific “roles” as roles in itself is a European concept.

The Complex Role

In Dr. Marie Ann Battiste’s article “Mi’kmaq Women – There Special Dialogue” we see a wonderful illustration of Mi’kmaq women in society, and it serves as an example of the complexity of Mi’kmaq women’s “roles” in traditional society, and how we will not a find a concise list of duties and expectations as you would see in European culture.

“In the traditional Mi’kmaq worldview, Mi’kmaq "woman" and "man" are the fulfillment of each other. Most of women's undivided obligations are held in common with their male partners. But Mi’kmaq thought teaches of special obligations which "women" have to the Holy Spirit. Mi’kmaq "women" are the keepers of the unknown. They have the ability to see the ordinary with amazement and to create the future. Each Mi’kmaq woman is the primal path that forces man beyond knowing to the unknowable future. In women, man finds what is beyond the daily struggle. Mi’kmaq women are the keepers of change.

They are the confirmation of the small and great rhythms of each generation to whom all return for comfort and release. They are the visible manifestation of continuity in change. Both continuity and change occur within a community in dialogue; thus the daily dialogues which occur in every facet of Mi’kmaq life essentially hold all visions of the future and the beauty of the past. Mi’kmaq women provide a special dialogue which is at the centre of the worldview. Knowing that all of nature is continually changing, the special dialogue of Mi’kmaq women conditions changes so it may be received within the worldview. Mi’kmaq women begin the dialogue with the future. They are the first teachers who transmit knowledge of the past and present to the future. They create an extensive, coherent, concrete tribal bond with the future through an easy silence and caring. The tribal bond arises from the rhythm of the daily event. Together-ness comes quietly in the shared trust inherent in family life"

(Battiste,1989).

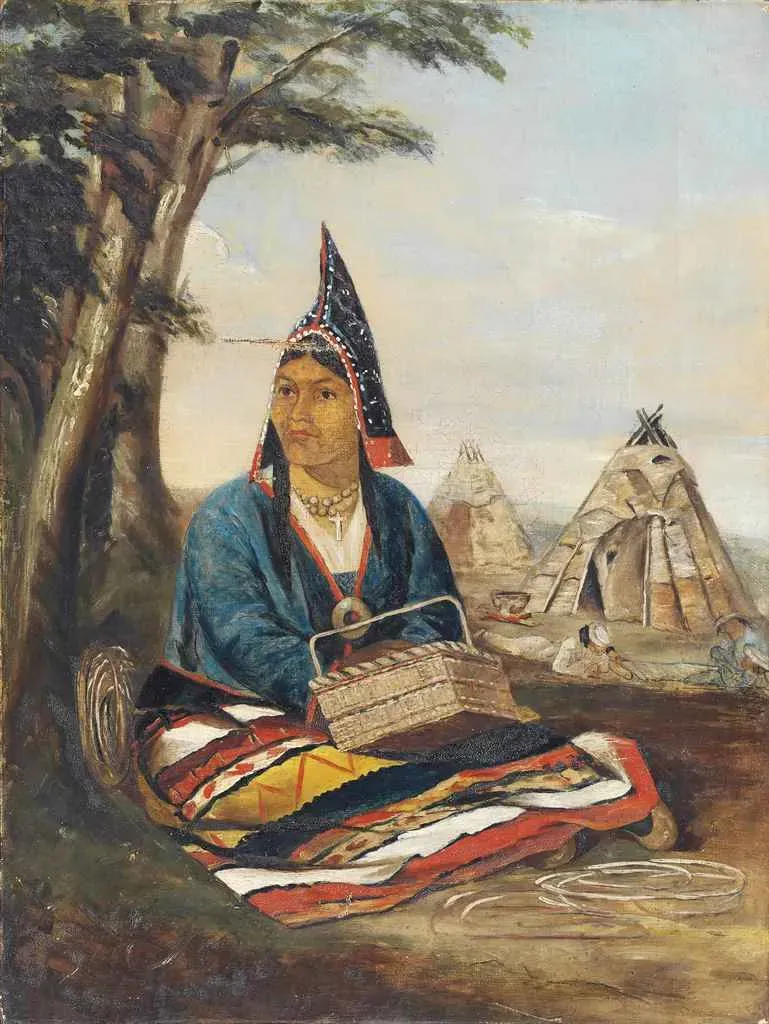

* Featured Art (top piece) by Mother & Daugher, Loretta & Shianne Gould.

** Featured Art (bottom piece) by Loretta Gould.

Customs and Beliefs Affecting Women

There are certain spiritual and cultural customs that affect Mi’kmaq women, particularly those surrounding their moon times. Women are not to take part in ceremony such as smudging or sweat lodges during this time, as their moon time is a natural cleansing gift from their ancestors. “The female of Mi’kmaq society is a powerful force, well-recognized among its people. She is a strong force for transmitting the values, culture and language of the people since she is the main agent of the culture. In every Mi’kmaq unit there is a strong female presence. The power of the woman and the cycles of her body are so strong, they could affect the spirits of the male so as to diminish his ability to hunt or fish. Certain customs are thus followed by women: they must not ever step over a male's legs, or his fishing pole (smkwati), his bow and arrows, his gun, or anything else associated with hunting and fishing” (Marshall, 1997).

A Spirit of Resiliency

“Mi’kmaq women represent a resiliency, so ill-defined by modern thought, but so well known in the hearts of Mi’kmaq’s. Throughout tribal and modern changes, from reserve like to modern life, and back to reserve life, Mi’kmaq grandmothers, mothers, sisters, and aunts typify a spirit of commitment, dedication, and physical and mental hardiness that allow the people as a whole to withstand economic hardships and social changes. Perhaps it is for this reason that Mi’kmaq people have weathered the contact with Europeans for so long” (Battiste,1989).

The Indian Act & Mi’kmaq Women

Women and the Grand Council

“The following view was presented in an interview with a Mi'kmaq woman closely associated with the Grand Council as a prayer leader and a protocol officer: What is the role of women in the Grand Council?”

“The role of women in the Grand Council is long and large. One of the things that the women do is organize, we organize everything. When I was a child, the women used to meet at the fire in Chapel Island. The island was arranged by community or village then, each had its spot and each had a fire. There was a main fire too. All the people from a village would use their own fire. It was at these fires that all the talking took place, and all the cooking would be done by women. The women would cook around the fire all day and talk about the problems on all their reserves. On the Saturday of the mission, they would meet in the church, and they would discuss the problems from each village, and then each fire would designate a woman to lobby the Grand Council members with these problems. Each woman, there would be about seven or eight chosen, would tell each member of the Grand Council what is wrong. So, each Keptin or council member would hear the same problem seven or eight times over - they still have great lobbying power today. Anyway, when the big meeting came about, there would be old women sitting at the parameters, and the old women would know the problems because they were at the church. The men would sit around inside the circle, the women never said anything while the meeting took place if they felt that the problems they had were brought forward in the men's meeting. However, if they were not, first one woman would clear her throat, and then another, and so on. The members of the Grand Council would know the women wanted something to be discussed, but they would not have to say anything” (MacMillan, 1996).

The Nova Scotia Native Women’s Association, in 1991, provided more insight into the roles of Mi’kmaq women on the Grand Council when they said...

“At one time, they had an elder, a grandmother involved in the decision-making process. One woman discovered through her own personal research; the consent of female elders was needed before Grand Council decisions were initiated. Another woman claimed that the role of women has dwindled. Native women are the caretakers of culture and traditions. There is a role to protect and ensure the recognition of women's rights as inherent and for the future.... because the Grand Council activities are more political than spiritual and that the Grand Council shouldn't discriminate against native women – their own people. We have elders in every organization, who can easily fit into the Grand Council” (Paul, C In Micmac News, 1991).

Nova Scotia Native Women’s Association

Today, there is much need for women in leadership, and women serving organizations. The Nova Scotia Native Women’s Association (NSNWA) is an organization that does just that. The Nova Scotia Native Women’s Association was formed in 1972, and in 1977 was officially incorporated as a not-for-profit association under the Societies Act of Nova Scotia. The NSNWA is mandated to help impower Indigenous women by being involved in developing and changing legislation, which affect them, by involving them in the development and delivery of programs promoting equal opportunity for Mi’kmaq women and their families. NSNWA is an inclusive provincial organization, speaking with a unified voice for Mi’kmaq and Indigenous women & two-spirit people both on and off reserve. NSNWA promotes equality and equal opportunities for Mi’kmaq and Indigenous women and educates women on their rights and the issues affecting them.

Additionally, NSNWA focuses on building relationships with all levels of government and other organizations to collaborate on socio-economic issues affecting the well-being of all Mi’kmaq women and their families. NSNWA works to alleviate the poverty of women and families, including food security and food sovereignty. Some current programs include sexualized violence prevention, client-centered support programs, reintegration support post incarceration, preserving cultural practices and traditions, education, employment, securing adequate housing, offering child and youth care, elimination of violence, domestic violence shelters, emergency housing support & loss prevention, health advocacy, housing research & development, MMIWG work, outreach, and other services that offer wrap around supports to Indigenous women. NSNWA offers crisis support and regular access to a culturally sensitive and trauma informed clinical therapist & other supportive programs and services through the Jane Paul Indigenous Resource Centre. The NSNWA operates as a grassroots organization that aims to address the needs of Indigenous women as they define them and works with them to identify gaps in services and supports and to address these gaps with a unified approach.

MMIWG

Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women and Girls is a human rights crisis, that is only beginning to be recognized in Canada is recent years. The harsh reality is that Indigenous women, girls, and two spirit people are disproportionately found murdered or gone missing in Canada.

There has been a national inquiry in 2015, that calls on the federal government of Canada to respond to this national tragedy. However, thus far the government of Canada’s response has been limited at best. In Nova Scotia, the province has committed to eliminating violence against Indigenous women, and are working with Indigenous groups such as the Nova Scotia Native Women’s Association to ensure Mi’kmaq consultation and leadership as they address the continued victimization of Indigenous women living in Canada.

Mi’kmaq Women Today

“Mi'kmaq women in our communities had very powerful positions. There was no question about it. You can still see that today. I am not talking about power over others, I am talking about power in strength and courage. It is putting yourself out there, it is doing what you need to keep the Nation going. Since before contact and through all the assimilation policies and the Indian Act and all the residential schools, Mi'kmaq women have always had this vision of keeping our Nation alive. We are always thinking about the future generations of our people” (2003). Mi’kmaq women have, and continue to be powerful contributors to Mi’kmaq society, and it is important to the Mi’kmaq nation to highlight this fact, and the government of Canada to recognize the importance of Mi’kmaq women in the future of this nation.

Conclusion

It is evident that the role of Mi’kmaq women had declined with European contact, but through female resiliency, and the determination to be heard, Mi’kmaq women have once again raised themselves in high regard, and are respected, listened to, and honored. However, it is clear the fight for Mi’kmaq women is far from over. We see today, the impacts of MMIWG, Gender Based Violence in Canadian society, and Indigenous women are the highest growing prison population in Canada. Unfortunately, Canadian society remains discriminatory and unjust to women, particularly Indigenous women. However, with the unity of strong Indigenous female voices, we are now rising to power in ways we never have in traditional times. There are now great female Chiefs, leaders, and change makers, and if history has taught us anything, it is that female resiliency will continue and grow throughout future generations.

Note: Much of Mi'kmaw history has been passed down through oral tradition. The stories and histories shared here are based largely on those oral accounts, which may vary slightly between communities, Elders, and storytellers. These variations are a natural and valued part of the oral tradition. If you have any questions about these histories, or would like to contribute with information passed down to you, please contact us at cdadmin@unsm.org.

MacMillan, Leslie Jane 1996, Mi'kmmey Mawio'mi: Changing Roles of the Mi'kmaq Grand Council from the Early Seventeenth Century to the Present

Tobin, Anita Maria, The Effect of Centralization on the Social and Political Systems of the Mainland Nova Scotia Mi’kmaq (Case Studies Millbrook 1916 & Indian Brook 1941), 1999

Battise, Marie Anne, Mi’kmaq Women – Their Special Dialogue, 1989

Bedwell-Doyle, Patricia – Address – Mi’kmaq Women and Our Political Voice, 2003

Paul, C Equality Not There - Gloade in Micmac News. November 21, 1991

Marshall, Murdena, Values, Customs and Traditions of the Mi’kmaq Nation, 1997

National Museum of the American Indian. Frederick Johnson Photograph Collection, Series 3: Canada: Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, Mi'kmaq (Micmac), 3.4: Eskasoni Reserve, Nova Scotia. Multiple items including N19860 and N19927. NMAI.AC.001.038. National Museum of the American Indian Archive Center, Smithsonian Institution.