The Lost Story of the 1759 Treaty

Hidden in the shadows of history, the 1759 Treaty with the Mi’kmaq remains one of the most elusive chapters in the Peace and Friendship story — a missing promise that continues to shape the legal and cultural landscape of Unama’ki to this day.

*Art is a depiction of Mi'kmaq Rock Art: Petroglyphs drawn by our ancestors that can be found within the boundries of Kejimkujik National Park & other Mi'kma'ki historic sites.

Peace & Friendship Treaties

It is widely understood that the Peace and Friendship Treaties between the Mi’kmaq and the British are a series of agreements spanning decades in the 1700s in an ongoing relationship between nations.

The Treaty of 1725 includes a provision that confirms Mi’kmaq liberties and properties will be preserved, an agreement that is renewed with each subsequent treaty.1

The Lost Declaration of Peace

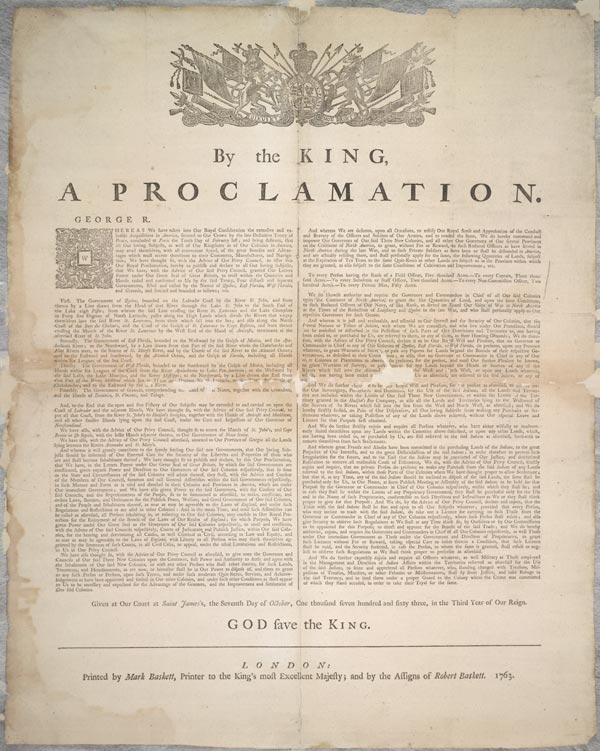

In 1759, a year after the Siege of Louisbourg, British General Edward Whitmore sent a letter to Father Maillard who was with the Mi’kmaq and French Acadians in Malogomich, or Pictou, that they were extending an olive branch under “the white banner of friendship”. In it, General Whitmore assured the Unama’ki, Piktuk aq Epekwitk and Eskikewa’kik Mi’kmaq that they would enjoy all of their possessions, liberty, and property with the fall of the French colonial government.2 General Whitmore wanted to secure peace with the Mi’kmaq through this transition of colonial powers with his letter reading as follows: 3

“I am commanded to assure you by His Majesty that you will enjoy all your possessions, your liberty, property with the free exercise of your religion as you can see by the declaration that I have the honour of sending you..."

It is believed that General Whitmore never attached the declaration of peace that he speaks of. Sakej Henderson and other researchers have never been able to find this elusive treaty with reasons for its vanishment unknown.

The result has been that both descendants of this treaty relationship have had to act on incomplete history, particularly as it relates to Unama’ki. Unama’ki was never specifically identified in any of the historic treaties with the British as this was a region subjected to French jurisdiction.

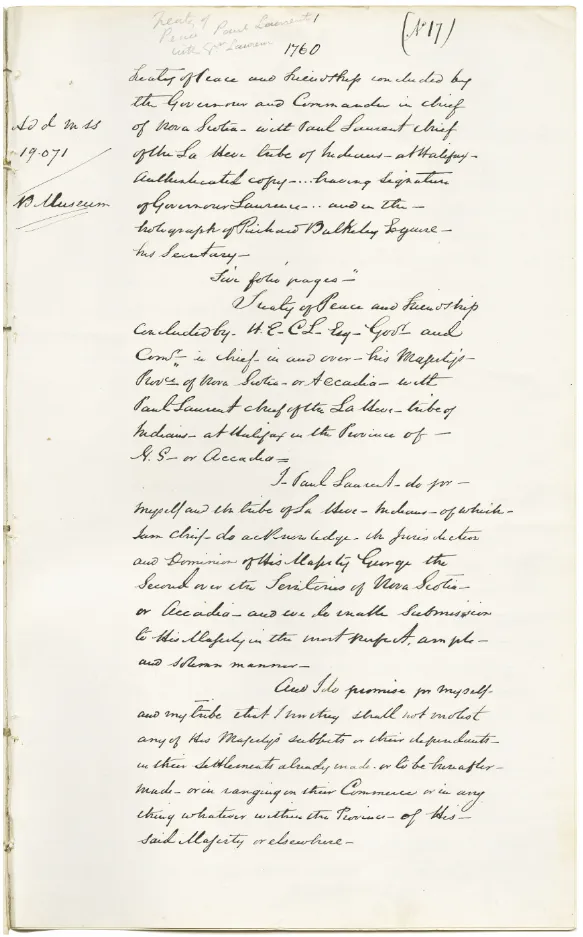

The La Have Treaty in 1760, an agreement between the British and the Passamaquoddy and Wolastoqey, has been used by the courts to interpret the suite of Peace and Friendship Treaties in an effort to find the Mi’kmaw perspectives of this period.4 But they operate on incomplete, one-sided information with no indication of the intent of the Unama’ki and Pictou Treaties of 1759. These treaty texts may never be found, but a recognition of their absence is just as important to the story of Unama’ki as the treaty itself.

Naiomi Metallic, Chancellor’s Chair in Aboriginal Law and Policy

“One issue with these unfindable treaties relates to the ‘balkanization’ we see in SCC case law around Mi’kmaq treaties - not seeing treaties assigned with the nation, but rather with individual groups from different parts of the nation. In Marshall 2, the Court seized on this to emphasize that people exercising their MLF rights would have to prove they descended from a group with such a treaty and were hunting in their territory (and authorized by the collective to exercise the right). Things like that put more pressure on us to have to find separate treaties related to different parts of Mi’kma’ki to claim rights. As argued by Jaime Battiste in “Understanding the Progression of Mi’kmaw Law” (2008) 31 Dal LJ 311 at 332, the British perception of local or individual treaty-making with small collectives of Mìgmaq “may be a Crown perspective, but it is not a shared understanding of the Mawio’mi. The Mawio’mi assert the core treaty is 1725–26 with the rest of the treaties ratifying or renewals of this treaty apply to all Mi’kmaq according to Mi’kmaq law...”

"More generally, it is unfortunate that incomplete records prevents us from having a clearer picture of the treaty relationship.

But I also wonder, based on the test for what constitutes a treaty discussed in Simon and Sioui, if despite there not being a written record, whether there could nonetheless be enough clear information to establish that there were solemn promises made by the British?”

Naiomi Metallic, Listuguj Mìgmaq First Nation

Chancellor’s Chair in Aboriginal Law and Policy & Associate Professor at Schulich School of Law

Note: Much of Mi'kmaw history has been passed down through oral tradition. The stories and histories shared here are based largely on those oral accounts, which may vary slightly between communities, Elders, and storytellers. These variations are a natural and valued part of the oral tradition. If you have any questions about these histories, or would like to contribute with information passed down to you, please contact us at cdadmin@unsm.org.

1. See 1725 Treaty text here: https://nbapc.org/treaty-of-1725/#:~:text=Saving%20unto%20the%20Penoscot%2C%20Narridgewalk,Privlege%20of%20Fishing%2C%20Hunting%20%26%20Fowling '

2. See Marshall Appellant Factum para 19; Wicken, William C. Mi’kmaq Treaties on Trial : History, Land and Donald Marshall Junior. Toronto, Ont: University of Toronto Press, 2002 at 194-195.

3. Marshall Appellant factum para 19

4. See R v Marshall 1999 3 SCR 456 and Simon v The Queen 1985 2 SCR 287.