What is The Grand Council?

The Mi'kmawey Mawio'mi or Mi’kmaq Grand Council is a spiritual and political body of the Mi'kmaq of the Atlantic provinces. It is an aboriginal construct governing the Mi'kmaq people and remains salient to Mi'kmaq culture and society today (MacMillian 1996).

Traditional Mi'kmaq Societal Structure

To better understand the role the Grand Council played in Mi’kmaq society, we must look at the traditional societal structure of the Mi’kmaq people. The Mi'kmaq nation had systems of polity, economy, religion, education and social behaviour. Although the Mi'kmaq were semi-nomadic, they exhibited a higher degree of sedentism than is usual among northern hunters and gatherers. Due to the expansive territory the abundance of diverse resources, and the ability of the Mi'kmaq to extract those resources they had a higher population density, this in turn required social and political organization beyond the local territory (MacMillan 1996). Mi’kmaq families often grouped together and lived in small nomadic communities. Several families grouped together and were referred to as bands, and each band was headed by a chief. Furthermore, “local bands were grouped together into districts."

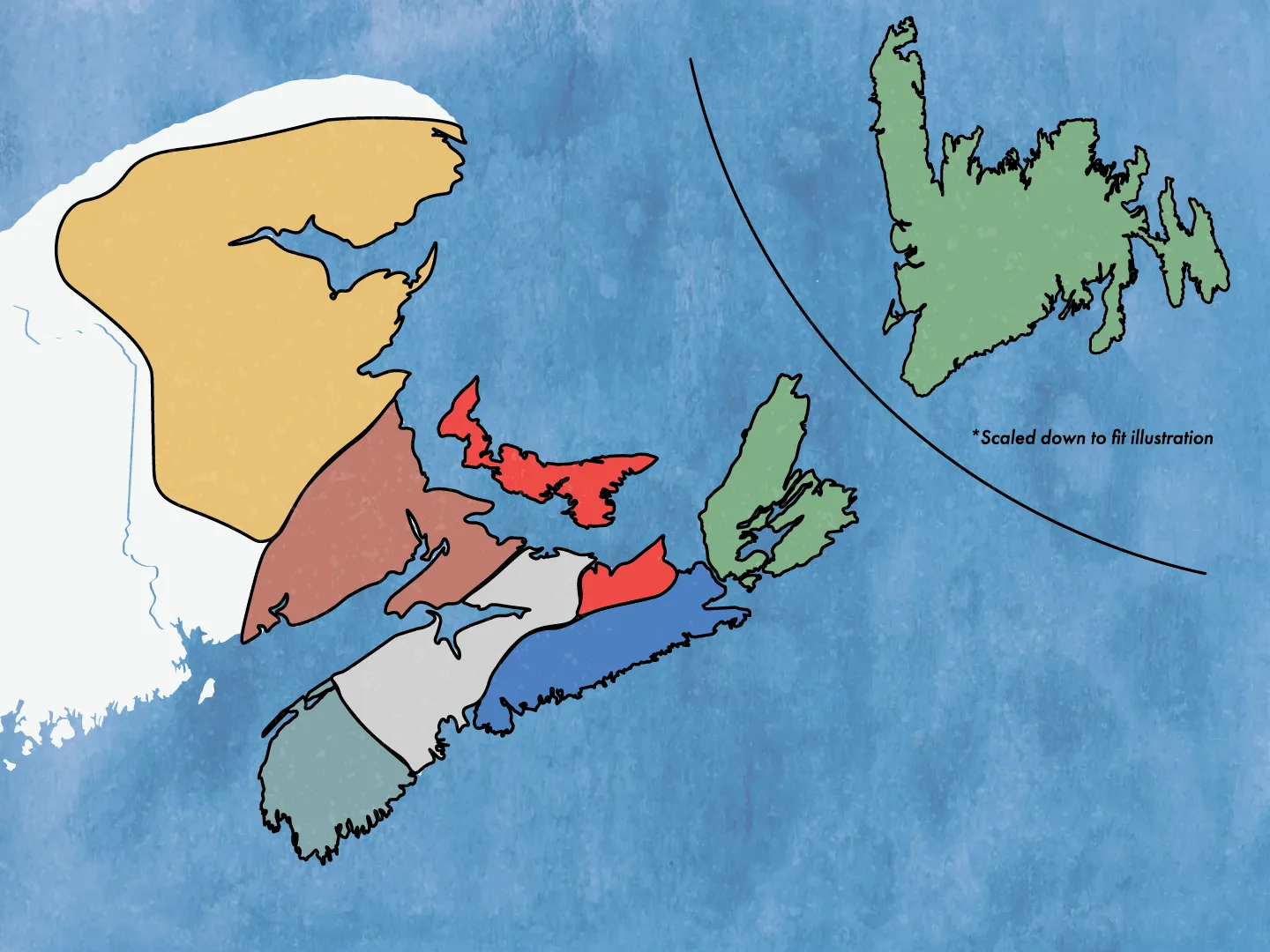

According to oral history, the Mi'kmaq nation was comprised of seven districts & each district had a head Sagamore”. Each district Sagamore belonged to the national political organization called Mi'kmawey Mawio'mi, or the Mi'kmaq Grand Council. The Grand Council was the apex of Mi'kmaq political organization” (MacMillian, 1996). The highest level of governance, however, was the Wabanaki Confederacy. The Wabanaki Confederacy included the Mi’kmaq, the Maliseet, the Passamaquoddy, the Penobscot, and the Abenaki Tribes.

The Seven Districts

Oral history tells us that Mi’kma’ki was divided into seven districts, but when these districts were formed is not entirely known. The districts were divided by geographical area.

*Hover over each district for more info

Roles of the Chiefs

*Reenactment of local Chief

District chief of Sipekn'katik - John Noel, 1829-1911

Grand Chief Membertou, 1507 - 1611

Choosing a leader

Chieftaincy was often inherited, and, in many cases, appointments were only a formality, as the position of Chief was normally passed on to the son of the current Chief. The eldest son would begin training at an early age in preparation for eventual succession. However, the eldest son had to be worthy of the Chief’s position, and if the successor did not posses the ability or qualities of the Chief role, the Council of Elders would choose another male successor typically from the same family group.

Respected Leadership

A good Chief would be expected to posses many qualities and leadership skills, including being fair, generous, a skilled hunter, a great warrior, great orator, and would be preferred to be older with more experience, and knowledge of healing & medicine. Specifically, the Chief had to have the respect of his people & accomplished this by meeting the needs of community members, and conducting himself in a dignified way showing intelligence, knowledge, and insight. It was also important the Chief inspire confidence in his people, by being a skilled negotiator, effective communicator, and have charismatic prowess. “Chiefs also had to set an example for their followers. It was important that chiefs did not accumulate material wealth because sharing among the Mi'kmaq was an important survival tactic and a way to ensure loyalty” (MacMillan, 1996).

Family Aliances

The Mi'kmaq often lived amongst extended family. "Nuclear families among the Mi'kmaq were grouped into living units of bilaterally extended families, with a tendency for these units to be patriarchal” (Miller, 1983). “People who were not blood relatives may have been present in these kin groups if they chose to align themselves with the head of the family, the Sagamore or Chief” (MacMillan, 1996) Furthermore, the Mi’kmaq practised polygyny, which also strengthen family ties & relations. This played a large role in Chieftainship because a larger family created a larger following and extended a Chiefs power by having a greater number of allies and connections. Additionally, the larger the extended family the more help in collecting and distributing goods and ensuring the health and wellness of the family and surrounding community.

“Religion and spiritual beliefs permeated all aspects of Mi’kmaq life. The duties of the religious leaders included predicting future events, directing hunters in the quest for game and curing the sick; possession of these abilities certainly raised a chief's status, prestige and influence” (MacMillian, 1996).

Conclusion

Although the population size of the Mi’kmaq Nation was not entirely known, (estimates vary) the population was large enough to require a more complex governance system than some other Indigenous tribes. The Mi’kmaq, prior to contact, were a healthy, wholistic nation, with a working governance structure with respected policies and procedures. Leadership, including the Grand Council, was respected, and members were expected to be established leaders and warriors who practised generosity, equality, and good judgement. The wholistic ideologies of the Mi’kmaq Nation enabled peaceful alliances with not only people, but also with nature and resources. This way of living, was sustainable, and successful for thousands of years.

Note: Much of Mi'kmaw history has been passed down through oral tradition. The stories and histories shared here are based largely on those oral accounts, which may vary slightly between communities, Elders, and storytellers. These variations are a natural and valued part of the oral tradition.

Miller, V.P 1983, Social and Political Complexity on the East Coast: The Micmac Case in The Evolution of Maritime Cultures on the Northeast and Northwest Coasts of America. R. J. Nash (ed), Simon Fraser University

MacMillan, Leslie Jane 1996, Mi'kmmey Mawio'mi: Changing Roles of the Mi'kmaq Grand Council from the Early Seventeenth Century to the Present