Grand Council's Diminishment of Political Power

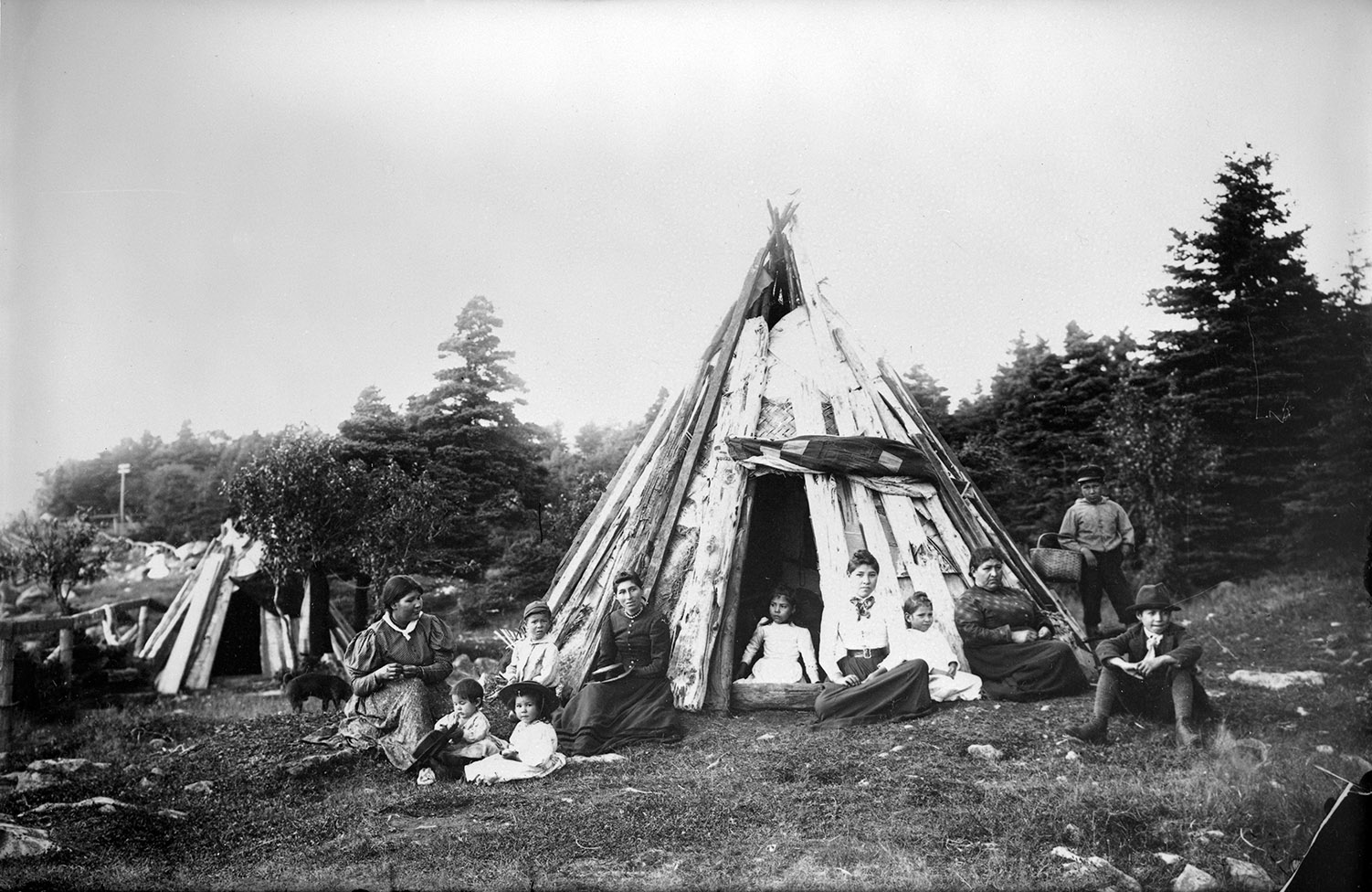

Once central to Mi’kmaq governance, the Grand Council saw its political power gradually eroded through colonization, religious conversion, and Canadian government policy. Explores how these forces reshaped Mi’kmaq leadership and culture—and how the Grand Council continues to hold cultural and spiritual significance today.

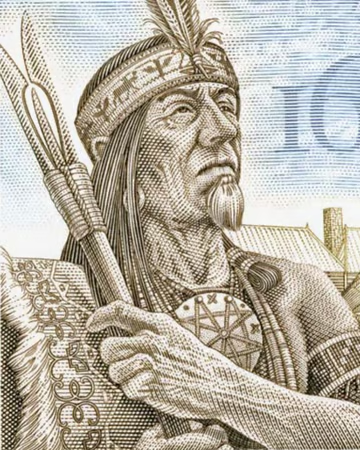

Grand Chief Membertou

A Turning Point

Early Impacts of Colonization

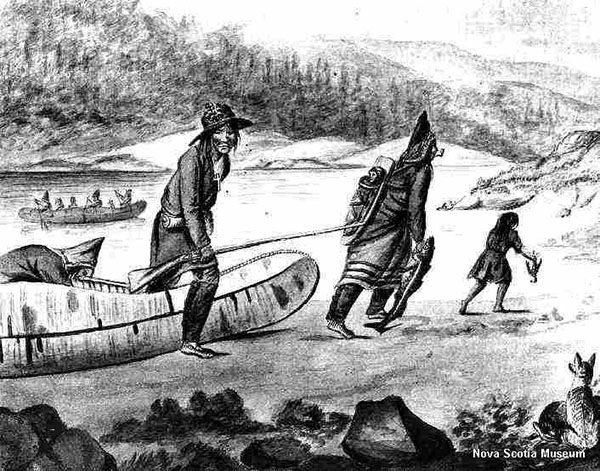

Many key factors of colonization played a crucial role in forever changing the Mi’kmaq way of life, and all factors are important in analyzing the diminishment of Grand Council authority, as the Grand Council and its practices are rooted in day-to-day lives of Mi’kmaq people. “Changes in the Grand Council were not immediate; rather, they evolved over time, dictated by necessity” (MacMillan, 1996).

Religion & Spirituality

Colonizing nations such as French and English did not recognize the Mi’kmaq practice of spirituality, rather they looked at spiritual practices as barbaric and uncivilized. However, “Mi’kmaq spirituality was part of the foundation for traditional socio-political organization. From spirituality, the natural order and the relationship between people and nature was established, a relationship based on respect and preservation. A fundamental element to the Mi'kmaq spiritually reverential system of governance was the belief in equality of all living things. This belief protected all resources and served as a basis for the continuation of the culture” (MacMillan, 1996).

Furthermore, settlers and missionaries took every opportunity to undermine Mi’kmaq spirituality, as a way of assimilation, and specifically sought to uproot their belief system to meet the French monarchy’s request to convert Indigenous people to Christianity. Overtime many spiritual practises of the Mi’kmaq people were unpracticed, and instead Christianity dogma was adhered to, even essential cultural practices such as burial and wedding ceremonies were altered. “The effects of conversion to Christianity were also beginning to dismantle Aboriginal Mi’kmaq social organization. Encroachment of settlers and the establishment of trading posts coincided with the location of missions. The Mi'kmaq began to move closer to the missions rather than remain at their traditional locations. There can be little doubt that aboriginal social binding mechanisms especially councils, weakened as the old kinship bases of local bands were destroyed in the new artificial settlements” (LeClercq 1910).

The conversion to Christianity by Grand Chief Membertou, and other Grand Council members and Chiefs significantly altered the purpose of the Grand Council in modern day and ultimately played a large role in diminishment of power. “The traditional political organization of the Grand Council did not have a religious role; it was only after conversion that such a role was created. Aside from local funerals, the Mission is where most people learn about the Grand Council; it is where the council is most visibly active, and this is why it is seen today as largely a spiritual organization” (MacMillan, 1996).

Technology & Trade

Another significant factor in the diminishment of Grand Council power, and the assimilation of Mi’kmaq people is the new-found reliance on settler technologies and trade. Specifically, the introduction of European foods, weapons, alcohol, and diseases were quintessential in the wellbeing of Mi’kmaq people and culture. Furthermore, as settlers did not have the same respect on nature and resources as Mi’kmaq people, the negative impacts on nature were catastrophic. Mi’kmaq principles of only taking what you need were not held by settlers, and this caused a quick diminishment of resources which led to further negative impacts on Mi’kmaq people.

“The Mi'kmaq developed a dependency on European goods, a dependency that altered traditional seasonal rounds and technologies. Attainment of furs by and for individual trade rather than for the chief eroded the position of the chief as middleman in Mi'kmaq trade with Europeans. As trade began to alter aspects of traditional society, the establishment of missions in Mi'kmaq territory significantly altered the spiritual context of Mi'kmaq leadership” (MacMillan, 1996). Given one of the key roles of the traditional Grand Council was to negotiate hunting grounds and territory, this settler ideology made this key responsibility obsolete. Furthermore, the reduction in population due to the negative impacts of contact reduced the number of Mi’kmaq people governed by the Grand Council and reduced the amount of individual’s who possessed knowledge of traditional governance practices.

Governance

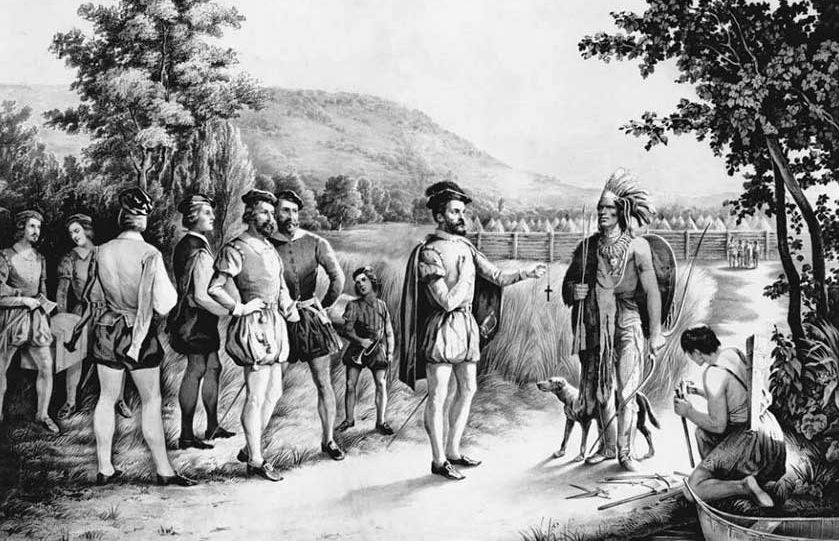

Another factor that decreased the power of the Grand Council, and other Mi’kmaq policies and practices was the fact that Europeans did not recognize Mi’kmaq law or governance practices.

According to MacMillian, “they did recognize that the Mi'kmaq had a form of government but discredited it because it was premised on egalitarianism rather than accumulation of wealth and coercive power in an individual or small unit. The Mi'kmaq Grand Council system was problematic for the Europeans because it was not based on a written legal code of conduct” (1996). It is clear that whether the Europeans recognized a working government system, they say the Mi’kmaq governance structure as inferior, and one that needed replacing.

*Art is an example of Mi'kmaq Rock Art, thought to be a represenation of the 7 districts and district chiefs.

Denial of Indigenous Land & World View

French colonists did not recognize the land as “owned” rather just occupied by the Mi’kmaq people, therefore according to colonial law, this land could be claimed as their own, and Indigenous people’s occupying this land were seen more as a resource or even a nuisance. The changes in traditional territory as resources were depleted or settlers’ occupation of land further depleted the resources of the Mi’kmaq people and ultimately the Grand Council.

Furthermore, societal changes such as the discontinuation of polygyny, due to the new practice of Catholicism, impacted Mi’kmaq family size, and ultimately declined Chief’s power and loyal followers. A declining population continued to add strain on an already struggling governance system.

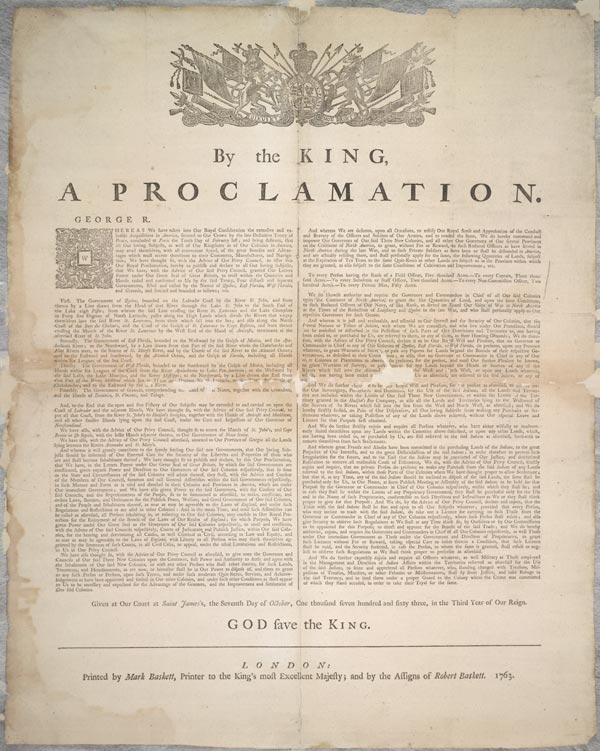

Later impacts of Colonization & The Indian Act

“The government of Canada divided Nova Scotia Mi'kmaq into twelve 'bands', further reducing the Mi'kmaq land base; it also set up the Indian Act chief system that still functions today. The Grand Council was not consulted on these major changes to the Mi'kmaq political and economic structure. Instead, Indian Affairs representatives told the Grand Council that they were no longer needed and would be replaced by band councils and elections. The Grand Council was scarcely recognized by the Canadian government” (MacMillan, 1996).

Grand Council Resiliency

Despite the horrendous challenges faced by the Grand Council, it still holds an important place in Mi’kmaq culture. Specifically, there are certain achievements accomplished by or in conjunction with the Grand Council that help shape Mi’kmaq culture and practices today.

Treaty Day

The Grand Council played a pivotal role in the celebration of Treaty Day. “In 1980, James Matthew Simon was charged under the Lands and Forests Act with being in possession of a shotgun and illegal shells in a closed hunting season. It has been suggested by some members of the Grand Council that this incident may have been an effort by the Grand Council to get treaty issues into court so that they could be validated, and the Mi'kmaq would have the economic opportunities promised in the treaties. Simon was convicted by the Nova Scotia Provincial Court and the decision appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada, which in 1985 upheld the validity of the Treaty of 1752 and acquitted Simon (UNSM, 1987) Treaty Day was established in celebration of this.” (MacMillan, 1996).

1988 Grand Council Mouse Hunt

“A further example of Grand Council involvement in treaty and aboriginal rights issues came in 1988 when several Grand Council members participated in a moose hunt to protest provincial efforts to curtail Mi'kmaq hunting rights” (MacMillan, 1996).

Mi'kmaq History Month

Finally, “observance of Treaty Day marks the start of another significant achievement of the Grand Council, Mi'kmaq History Month. October in Nova Scotia has been set aside for promoting and educating people about Mi'kmaq history, life ways, traditional government, and language and culture. Mi'kmaq History Month is a joint effort of the province and the Grand Council and involves all Mi'kmaq organizations and agencies. Not only does this month help to educate Mi'kmaq people about themselves, but it also helps non-Natives to understand what being Mi'kmaq is all about” (MacMillan, 1996).

Conclusion

The impacts of colonization on the Grand Council’s political authority are evident. The adversities faced by the Mi’kmaq people were both harsh and deliberate. “As the Canadian government-initiated policy after policy of assimilation, and undermined traditional forms of Mi'kmaq government by imposing a system of elected chiefs and band councils, the Grand Council shifted and adapted to meet these pressures” (MacMillan, 1996). The fact that the power of the Grand Council diminished following contact is in direct correlation with the loss of power of Mi’kmaq people. Some may look to blame Catholicism and Chief Membertou’s baptism, but evidence suggests this is only a fraction of the reason for the Grand Council’s decline of influence on Mi’kmaq government practices, and it is truly the impact of colonization that undermined the power of the Grand Council.

Note: Much of Mi'kmaw history has been passed down through oral tradition. The stories and histories shared here are based largely on those oral accounts, which may vary slightly between communities, Elders, and storytellers. These variations are a natural and valued part of the oral tradition. If you have any questions about these histories, or would like to contribute with information passed down to you, please contact us at cdadmin@unsm.org.

MacMillan, Leslie Jane 1996, Mi'kmmey Mawio'mi: Changing Roles of the Mi'kmaq Grand Council from the Early Seventeenth Century to the Present

Lescarbot, Marc 1609 The History of New France. (Reprint 191 1-14) Three Volumes. Toronto: The Champlain Society 19 1 1. Greenwood reprint 1968.

LeCIercq, C. 1691 Nav Relations of Gaspesia, with the Customs and Religion of the Gaspesian Indians (reprint, 19 10) Toronto: Champlain Society.

Union of Nova Scotia Indians 1987 The Mi'kmaq Treaty Handbook. Sydney: Native Communications Society of Canada.