The Unfolding of Centralization

To examine the “experiment” of centralization, we must first take a closer look at Mi’kmaq history prior to contact, and the succession of changes that took place following the settlement of Europeans in Nova Scotia. The timeline show’s that although the idea of Centralization doesn’t get recognized in Nova Scotia until the creation of the Centralization Policy for the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia in 1910, the stage was set for centralization and assimilation shortly after European contact.

Mi'kmaw Artist Alan Syliboy

Before 1496

Pre-Contact

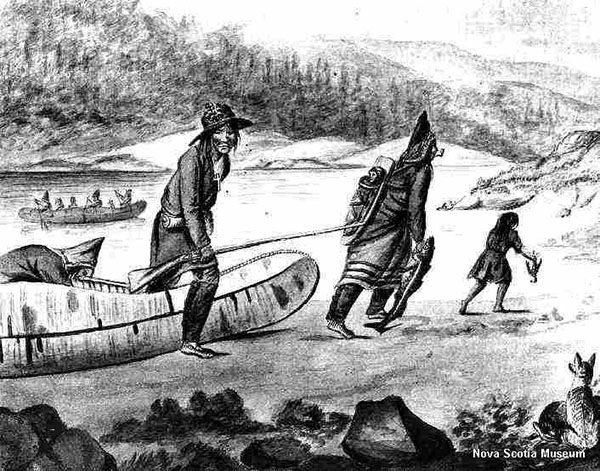

Prior to contact the Mi’kmaq people had a thriving society, with a government structure, a holistic ideology, and a deep-rooted respect for the natural world. Mi’kmaq people thrived in nomadic communities, hunting, fishing, and living off the land, never taking more than what was needed, in the practice of netukulimk. Everything needed for a successful life was received from the land including medicines, food, water, shelter, clothing, and spirituality. Mi’kmaq people lived in the Atlantic region for thousands of years, and were a sovereign, independent people.

1496 - 1605

Contact

According to known history, John Cabot was the first European contact in North America in 1496, with exception to Norsemen who established a settlement in modern day Newfoundland around the year 1014. However, it wasn’t until 1605 that French colonists established their first settlement in Port Royal in the maritime provinces including Nova Scotia. Originally, the Mi’kmaq made strong alliances with the Acadians and there was cooperation and support between Mi’kmaq people and settlers, they even recognized Mi’kmaq people as an independent nation, as they created treaties and agreements. However, as more settlers arrived, this recognition & agreements declined rapidly.

1610

End of the 15th Century

During the end of the 15th century more and more European settlers were arriving on traditional Mi’kmaq land. During this time European’s were competing for land and resources, and as European explorers “discovered” land, they would claim this already occupied land in the name of their nation. Furthermore, Europeans also did not hold the same respect for nature as Mi’kmaq people and quickly extinguished resources by overfishing, hunting, and gathering. Europeans also brought modern weapons, diseases, and alcohol, further changing the Mi’kmaq way of life. Additionally, Europeans did not honor Mi’kmaq spiritual beliefs and forced conversion to Christianity starting in 1610 with the conversion of Grand Chief Membertou (MacMillan, 1996). This ultimately impacted the Mi’kmaq governance system, as “, “they did recognize that the Mi'kmaq had a form of government but discredited it because it was premised on egalitarianism rather than accumulation of wealth and coercive power in an individual or small unit” (MacMillan, 1996).

1763

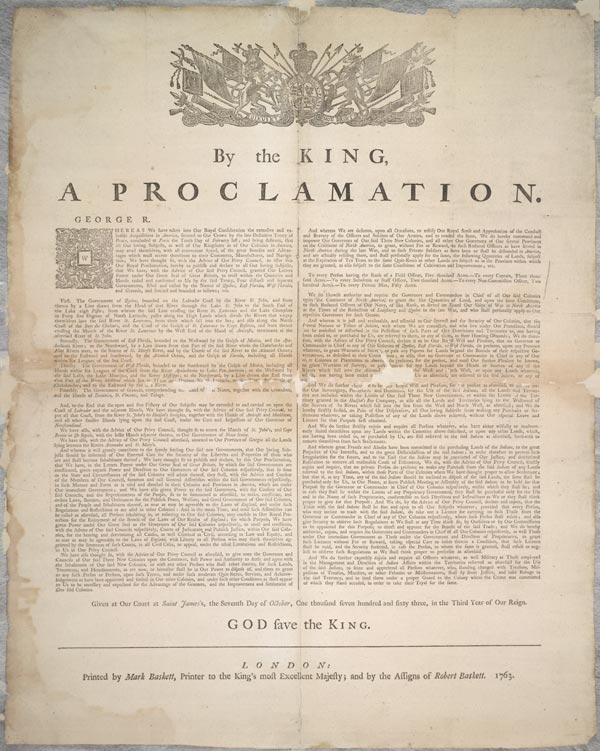

Royal Proclamation of 1763

During the Royal Proclamation of 1763 King George the Third said Indigenous nations own their land and that the only way settlers could own this land would be through treaties and negotiations with Mi’kmaq people. However, this promise was short-lived, as settlers often viewed Mi’kmaq people as a threat to expansion and used extreme measures to drive them off their lands, including violence & genocide. The British North American Act, directly in conflict with the Royal Proclamation, came into effect a little over 100 years later.

1867

British North American Act

“In 1867, when the British North American Act gave the federal government the authority to legislate on matters relating to ‘Indians and Land Reserved for Indians,’ Nova Scotia was relieved of the responsibility for the 1600 Indians there” (Patterson, 1985). However, during this time in history, despite contact with the Europeans for over 100 years, Mi’kmaq people continued to sustain their nomadic lifestyle and keep cultural and traditional practices part of their day-to-day lives.

1876

The Indian Act

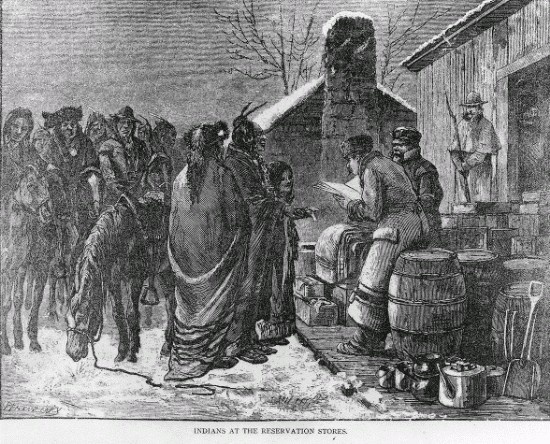

“The implementation of the Indian Act in 1876 was likely the most severe blow ever to Mi'kmaq society politically, economically, spiritually and culturally” (MacMillan, 1996). The Indian Act separated Mi’kmaq people onto reservations, removing them from their traditional homelands, putting them under complete government control. Indian agents monitored every aspect of their lives, including restricting travel, providing extremely limited financial aid, limited hunting and fishing, and outlawed spiritual ceremonies like potlach, pow-wows, and Sundance. Through the enforcement of the Indian Act Indigenous peoples were denied basic human rights. With the Indian Act also came Enfranchisement, which under federal policy dictated that all First Nation’s people who went to university lost their “legal Indian status”. With Mi’kmaq “out of sight, out of mind” on reservations, the government of Canada was responsible for almost every aspect of Mi’kmaq life, including financial responsibility, now that the Mi’kmaq people were no longer allowed to fend for themselves.

Assimilation

The government of Canada truly thought the “Indian Problem” would solve itself as more and more Mi’kmaq succumbed to diseases, poverty, and were enfranchised into Canadian society.

As Indian Affairs deputy superintendent Duncan Campbell Scott said in 1920, “I want to get rid of the Indian problem, our (government of Canada) objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian Question and no Indian Department” (National Archives of Canada).

This quote illustrates the fact that the government of Canada did in fact view the Mi’kmaq people as a problem. Specifically, they were seen as a problem because after being put onto reservations the Mi’kmaq people relied solely on the government of Canada for support and were therefore seen as a monetary drain on the system. It was the goal of the government of Canada to have the Mi’kmaq people die from poverty and disease or assimilate into Canadian culture, ultimately losing all sense of identity.

Residential Schools

Residential schools were a method utilized in assimilation. From the mid-1800s until the 1990s, the federal government ripped Indigenous children from their homes and communities and put them in boarding schools that were run by churches. In Nova Scotia Shubenacadie Indian Residential school operated until 1967, causing surmounting trauma, that is still recognized today in future generations of Nova Scotia Mi’kmaq. Those who escaped boarding schools were sent to Indian Day school.

In these “schools” as well as Residential Schools, children were forced to learn colonialized world views and abandon all recognition of their culture. They could not speak the Mi’kmaq language, could not practice ceremony or tradition, and if they were caught participating in an outlawed activity punishment would be harsh and swift. Having no loving family to demonstrate healthy relationships, when residential schools finally did close, those who returned to community had a loss of family, community, cultural knowledge and suffered with complex trauma due to the horrendous environment of residential schools.

1917

Centralization - Millbrook First Nation

Following the explosion of a munitions ship in Halifax harbour in 1917 many Mi’kmaq were moved to Millbrook First Nation. This occurred in part due to complaints from settlers, as following the explosion Mi’kmaq were supposedly living in shacks and falling down buildings along the railway tracks close to Dartmouth and Halifax (Patterson, 1985). The government of Canada did not want these “undesirables” living in and around busy urban areas. Therefore, it was proposed to move the Mi’kmaq people living in these areas to Shubenacadie, however, “the Indians refused to cooperate because it was too isolated” (Patterson, 1985). Ultimately, “in 1919, most of the surviving Indians were moved to the Millbrook Reserve” (Patterson, 1985).

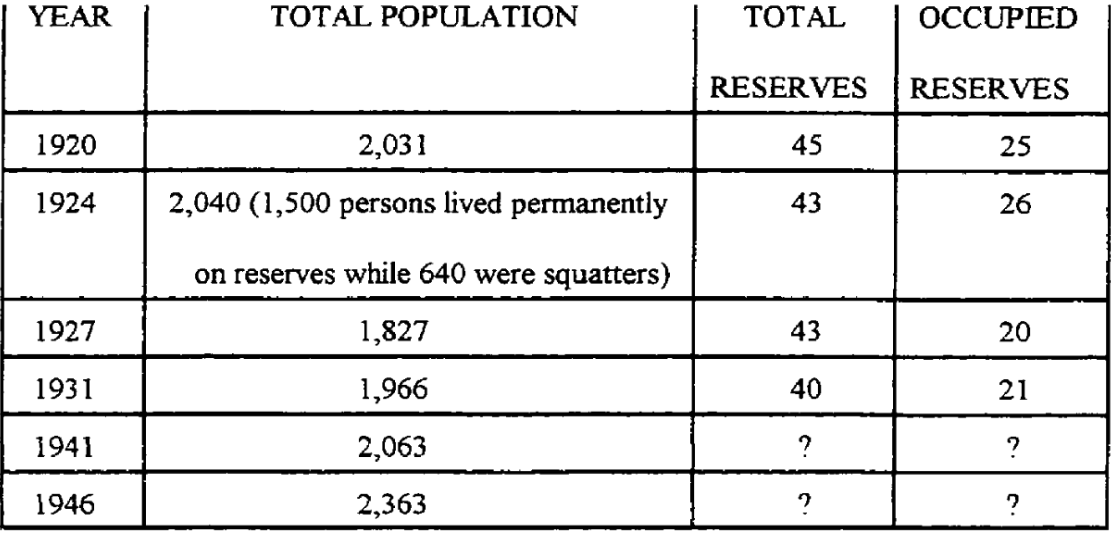

“Within a century of Jaques Cartier’s first voyage in 1534, 75 percent of the Micmacs perished” (Patterson, 1985). The featured table is referenced by Patterson and outlines the past population statistics in Nova Scotia prior to centralization.

1918

Development of the Concept of Centralization

It was following the first world war, “in the spring of 1918, during the financial crisis, that the concept of centralization was first expressed. At the behest of the Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs, Duncan Campbell Scott, an investigation into the cost of replacing Nova Scotia’s nineteen agencies with four was launched” (Patterson, 1985). This suggestion was based with the goal of saving money, and “calculations showed a saving of $200.00 per year with only 3 full time Indian agents” (Patterson, 1985). Research suggests that this idea was not mobilized in its entirety because when the first world war ended in 1918 there was less financial strain, and therefore, less need to cut spending.

1942

Centralization Policy of 1942

In 1942 the Department of Indian Affairs attempted to implement a Centralization Policy. In Nova Scotia, Mi’kmaq were to move to two central reserves, one in Sipekne’katik in mainland Nova Scotia, and one in Eskasoni in Unama’ki (Cape Breton Island). “By collecting them at two central locations, the government expected to reduce costs for Indian welfare, education and health care, ease local complains; and give Indian affairs, the clergy, and the RCMP greater control over Indian life” (Patterson, Lisa, 1985) By 1942 the idea of Centralization seemed highly advantageous to the government of Canada, as World War two had significantly decreased the economy of Canada, and the government was looking at any way to save money. This was further supported by Arneil’s Investigation Report on Indian Reserves and Indian Administration (Patterson, 1985). “The most grievous error in Arneil’s report was his assumption that the Indian population of Nova Scotia would not expand”, when in fact the population grew exponentially (Patterson, 1985). The government’s goal of saving money though centralization turned out to be an utter failure, as “welfare costs rose sharply because Indians isolated at Eskasoni and Shubenacadie found it virtually impossible to find work in a province whose economy continued to decline throughout the fifties” (Patterson, 1985).

What was promised

The government of Canada promised if the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia agreed to centralize that they would find finished houses, employment opportunities, health services, and safety. Additionally, the government of Canada attempted to make centralization more enticing by controlling media reporting on the topic. They had the media release articles insinuating that life on reservations was thriving and desirable, an example of this is the release in Sydney Post-Record entitled “Eskasoni – Village turned into Model Community” (Patterson, 1985).

Unfulfilled Promises & No Turning Back

The Mi’kmaq who did move to “central” reservations were met with incredibly disappointing circumstances. Houses were incompetent, work was scarce, and no health care was available. Furthermore, to ensure families could not return to their original communities Indian Agents often burned their houses to ensure they had no where to easily return. As tensions grew higher “R.C.M.P protection was formally requested on reserve” (Patterson, 1985).

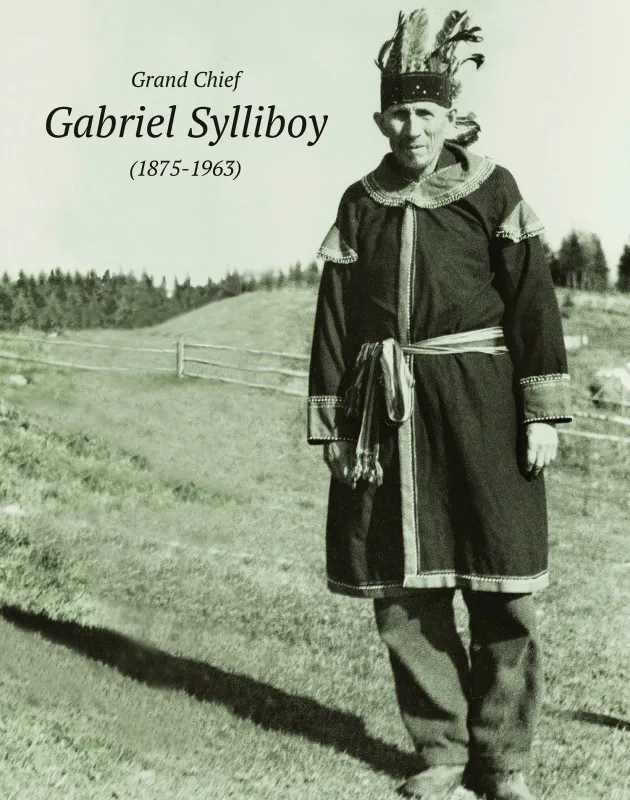

The Fight Against Centralization

Many Mi’kmaq people protested centralization, these included Gabriel Sylliboy, Ben Christmas, John S. Googoo, and many others. “Close to one hundred Indian names were attached to a petition dated 26 May 1942 from the Middle River (Wagmatcook) reserve protesting the move as unfair and of benefit to no one” (Patterson, 1985).

Furthermore, the “Victoria County Liberal Committee sent a telegram in support of Middle River to Matthew MacLean M.P. (Cape Breton North-Victoria) stating ninety percent of the Indians and other citizens are opposed to it”. Despite the evident opposition, the government of Canada pursued centralization and threatened force if necessary. Specifically, if the Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia did not agree to do what was requested by Indian Agents, they were under threat of losing their status and government financial support (Tobin, 1999).

Quietly Abandoned

“It is difficult to document the precise moment at which the policy of concentrating the entire Indian population at Shubenacadie and Eskasoni was actually abandoned. Correspondence for the year 1949 does make it clear, however, that under a new Director, a new Minister, and new Prime Minister, total relocation ceased to be the department’s goal. The seventh full year of centralization was therefore it’s last” (Patterson, 1985). It seems that there are many contributing factors as to why centralization failed, one being the government not anticipating facing the strong opposition of Mi’kmaq people.

Ultimately, “the centralization scheme lacked the financial backing it required to even approximate the form imagined by its proponents; moreover, the Indian’s natural resistance to being uprooted from their homes was reinforced by the plan’s obvious infeasibility. Their reluctance to move, and the problems that occurred when they did or did not, must be included in the reasons for the termination of the policy - even though Indian resistance counted for absolutely nothing until well after the war” (Patterson, 1985).

Conclusion

The sad reality is, that research on the centralization of Nova Scotia Mi’kmaq is very limited since archival records were only kept by Europeans, and some belonging to the Romain Catholic Church have not been released. Most accounts from the Mi’kmaq perspective are recorded letters that were sent in opposition of centralization, or pleas for support from the government. However, Mi’kmaq mostly passed down the impacts and details of centralization by passing on knowledge orally by those who experienced it firsthand. There are many powerful stories told by Mi’kmaq Elders and knowledge keepers of life during the time of centralization, and most relay more gruesome details that have never been recorded under official records.

Note: Much of Mi'kmaw history has been passed down through oral tradition. The stories and histories shared here are based largely on those oral accounts, which may vary slightly between communities, Elders, and storytellers. These variations are a natural and valued part of the oral tradition. If you have any questions about these histories, or would like to contribute with information passed down to you, please contact us at cdadmin@unsm.org.

National Archives of Canada, Record Group 10, vol 6810 file 470-2-3, vol 7-55 (L-3) and 63 (N-3)

Patterson, Lisa Lynne, Indian Affairs and the Nova Scotia Centralization Policy, 1985

Tobin, Anita Maria, The Effect of Centralization on the Social and Political Systems of the Mainland Nova Scotia Mi’kmaq (Case Studies Millbrook 1916 & Indian Brook 1941), 1999

National Museum of the American Indian. Frederick Johnson Photograph Collection, Series 3: Canada: Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, Mi'kmaq (Micmac), 3.4: Eskasoni Reserve, Nova Scotia. Multiple items including N19860 and N19927. NMAI.AC.001.038. National Museum of the American Indian Archive Center, Smithsonian Institution.